A Year's Planning

Events leading up to Normandy: Germany invaded much of Western Europe in the spring of 1940. A narrow stretch of sea, the English Channel, was all that separated the surging enemy forces and Great Britain, but the island nation held firm. An Allied raid on the French coast at Dieppe in August 1942 resulted in heavy losses, especially for Canadian troops. They learned that to win the war, Germany would have to be defeated on the ground in Western Europe and 1944 would be the year the Allies would strike back.

The target for the Allied landing forces would be the beaches of Normandy in France. Planning and preparation for this immense undertaking, code-named Operation Overlord, began more than a year earlier. Without an exact date scheduled for the attack, the terms ‘D-Day’ and ‘H-Hour’ were used for planning purposes. Land, sea and air forces trained extensively and the necessary troops, ships, tanks, supplies and other equipment were steadily amassed. Long flexible pipes, nicknamed “PLUTO” (pipelines under the ocean), were designed to carry fuel under the English Channel.

Crews pored over maps, photographs and three-dimensional models of the invasion beaches. These showed the layout of the Normandy coastline and key landmarks — houses, church spires, headlands — so that every officer, airman and soldier knew their objectives and what awaited them.

By May 1944 the Allies were ready but they had to wait until the weather, tides and phase of the moon were right in order to be able to attack.

.jpg)

Secrecy Was Key

Secrecy was deemed essential to the success of the Allied landings at Normandy. Misinformation was deliberately leaked to the Germans to confuse them over where the landings would actually take place. This deceptive plan was code-named Operation Fortitude.

A dummy army of inflatable, wooden and paper maché tanks, trucks and other equipment was built in southeast England. From the air, German reconnaissance planes would believe that a gigantic army was being organized just across the English Channel from Pas-de-Calais, France, some 375 km north of the beaches at Normandy. Meanwhile, the real invasion force was assembled in southwest England, and the entire area was sealed off by military authorities.

Some Germans officials heard chatter that the attack was to be at Normandy, but they were convinced that any landing in Normandy was merely a diversion from the main attack planned at Pas-de-Calais. To add to the Germans’ confusion, a few hours before D-Day, the Allies started a series of maneuvers opposite Pas-de-Calais, indicating that a large-scale amphibious allied attack was to begin. This was coupled by an aerial bombardment over Pas-de-Calais. As a result, the German generals chose to keep 150,000 men of the 15th Army in Pas-de-Calais rather than send them to fight in Normandy.

Operation Fortitude was deemed a major success.

Timing was everything

D-Day had been postponed repeatedly since May, 1944 mostly because of bad weather. Potential invasion dates were a precious few. The Allies needed a full moon to illuminate obstacles and landing places for gliders; and a low tide at dawn to expose the elaborate under-water defenses installed by the Germans.

June 5 was chosen by Allied Supreme Commander Dwight Eisenhower to be D-Day. It was the first date in a narrow three-day window with the necessary astronomical conditions. The massive Normandy landings, however, also required optimal weather conditions. High winds and rough seas could capsize landing craft and sabotage the amphibious assault; wet weather could bog down the army and thick cloud cover could obscure the necessary air support. Stormy weather on June 5 forced Eisenhower to reluctantly delay D-Day by 24 hours.

Allied meteorologists predicted a break, small though it was, for June 6. Eisenhower launched the invasion with a simple: “Okay, we'll go.”

Without that small break in the weather, D-Day would have been put off two more weeks until the tides and the moon were right again.

A little help from our friends

The Allies needed the help of the French Resistance networks during and after the preparation of the Normandy invasion. Intelligence was transmitted to the French Resistance via the radio. The British Broadcasting Corporation sent pre-arranged coded messages during its broadcasts to the volunteer members of the French Resistance in German-occupied France. Every message had a meaning and purpose. Five days before June 6, 1944 (D-Day), the first three lines of the “Chant d’automne” poem of Verlaine (“Les sanglots longs – Des Violons – De l’automne…”) were broadcasted.

The meaning of this message was: The landing will happen this week and once the three next lines of this poem are broadcasted (“Blessent mon coeur – D’une langueur – Monotone…”), the offensive will start 48 hours later.

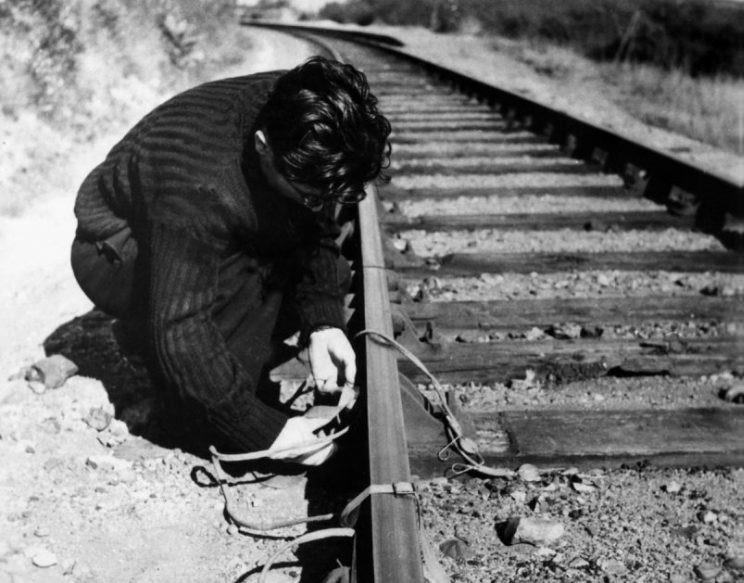

These messages were a call to action. Members of the resistance movement destroyed railroads, telephone lines and installed anti-tank mines on the roads in advance of the landing. The night between June 5 and June 6, 1944, nearly 1,000 sabotage actions were carried out by the French Resistance in order to weaken counter-attacks by the Germans.

Sources: Juno Beach Centre, Veterans Affairs Canada and the Imperial War Museum.