This exhibit explores the history of the Spanish Flu and other medical events that impacted Okotoks, and also salutes the medical professionals who keep our community healthy.

Okotoks was greatly affected by the Spanish Flu of 1918-19 which killed as many as 50 million people world-wide. Alberta recorded 38,308 cases and 4,380 deaths in 18 months. Masks became mandatory, gatherings were banned and even public opposition occurred during the three waves of the Spanish Flu. Sound familiar?

Scroll down for Part 2 -The Spanish Flu’s Impact on Okotoks.

Part 1 – The Spanish Flu: What, Where, When and Why

The Spanish Flu of 1918-19 killed between 20 and 50 million people worldwide, including between 30,000 and 50,000 Canadians.

Alberta recorded 38,308 cases of the Spanish Flu and 4,380 deaths in the 18 months that the flu took its course.

Where did it come from?

Researchers have debated the source of the Spanish Flu for decades – but all agree it did not originate in Spain. It earned that name because the Spanish press were the first to publicize news of the mysterious, deadly flu killing hundreds of people. The source of the outbreak focuses on four possible locations: England, France, China or the United States.1 Most researchers now believe it was an H1N1 virus (avian flu) that originated in Camp Funston, a U.S. Army Camp in Kansas. The virus spread to the frontlines when the troops went overseas and then it spread back to their hometowns once troops returned home.2

The Three Waves of the Influenza

In southern Alberta, the first wave began Oct. 2, 1918 and lasted 51 days. The second wave started Dec. 11, 1918 and lasted 47 days. The third wave lasted about a month, from the end of March until April 25, 1919.3

The first wave arrived in the Calgary area on Oct. 2, 1918, believed to be from returning troops on board the 3 am train travelling from Regina to Calgary. A telegram from Regina alerted local health officials that there were sick soldiers on the train.4 Although the infected soldiers were isolated once they arrived in Calgary, it had already spread to others on the train who, upon their arrival, dispersed to their hometowns across southern Alberta. The flu spread rapidly.

Symptoms

The Spanish Flu triggered a sudden onset of symptoms that included a temperature of 101-103F, fatigue, cough and signs of upper respiratory infection. Many of those affected were between the ages of 20 and 40. Recovery (or death) typically came after seven days. Death resulted if the Spanish Flu led to pneumonia.

Restrictions

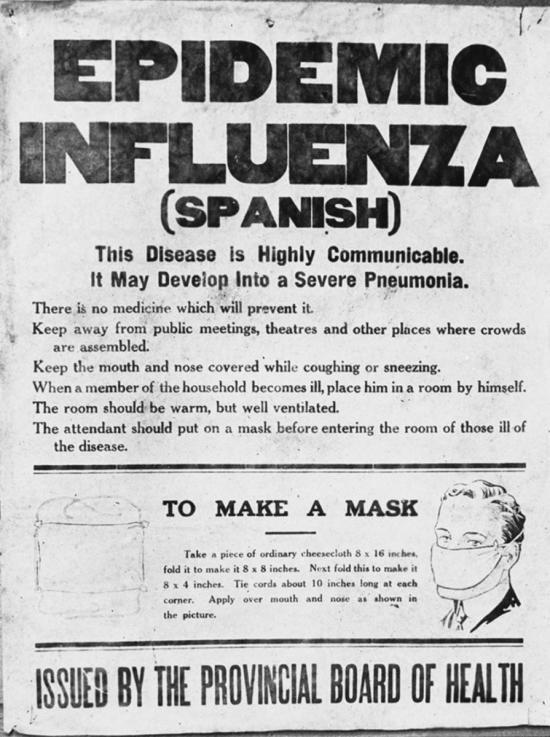

Within 10 days of the arrival of the first wave in Alberta, health officials banned gatherings at churches, schools, theatres and public places.

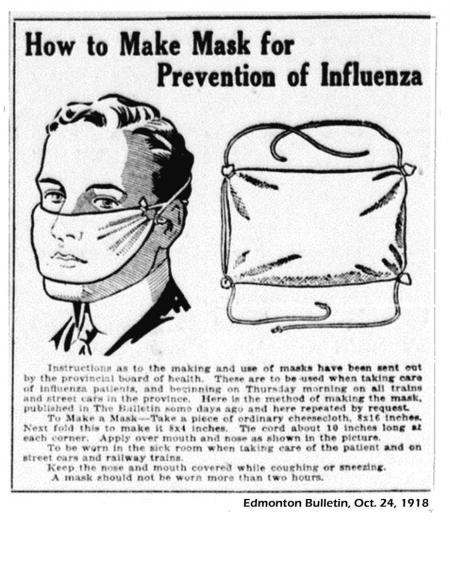

The wearing of masks was mandatory first on trains and Calgary street cars. Then on Oct. 25, masks became mandatory anytime anyone went outside of their home. On Oct. 30, non-essential stores closed. (They reopened on Nov. 23 after the first wave subsided). Some churches in the City of Calgary circulated pamphlets condemning their closures.

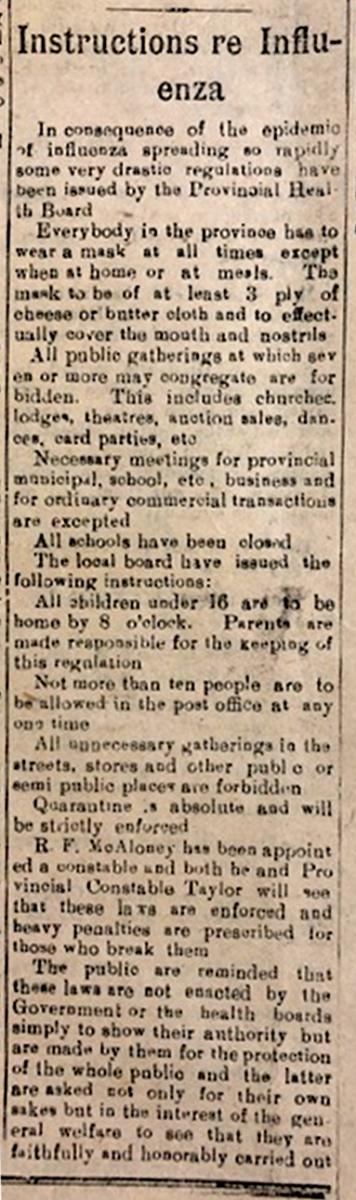

On Nov. 18, 1918, the Okotoks Board of Health held an emergent meeting and, in keeping with provincial regulations, Okotoks officials declared that:

- Masks are to be worn at all times except for when at home or at meals.

- Masks are to be made from at least three-ply cheesecloth or butter cloth and cover both mouth and nostrils.

- All public gatherings of seven people or more are prohibited including churches, lodges, dances, theatres and card parties.

- All schools closed.

- All children under the age of 16 are to be home by 8 pm.

- No more than 10 people allowed at one time in the post office.

- All unnecessary gatherings in streets, stores, and other public and semi-public places are forbidden.

- Quarantine is absolute and will be strictly enforced.5

Enforcement

Enforcing the restrictions was the responsibility of each municipality. Okotoks Council appointed R. F. McAloney as a constable to assist Const. Taylor of the Alberta Provincial Police to “see that these laws are enforced for those who break them.” Okotoks Council further reminded the public that “these laws are not enacted by the government or the health boards simply to show their authority but are made by them for the protection of the whole public and the latter are asked, not only for their own sakes, but in the interest of the general welfare to see that they are faithfully and honourably carried out." 6

Treating those who were sick also fell on cities, towns, families and individuals — there was no assistance from the either the federal or provincial governments. Treatment consisted of quarantining the patient and keeping them comfortable. There was no vaccine.

1 The Canadian Encyclopedia, 1918 Spanish Flu in Canada, article by Janice Dickin, Patricia G. Bailey, Erin James-Abra, March 18, 2020

2, 3, 4 The 1918-19 Spanish Flu in Alberta, J. Robert Lampard, Alberta Doctors’ Digest, May-June 2020.

5, 6 Okotoks Review newspaper, November 1918.

Part 2 -The Spanish Flu’s Impact on Okotoks

Caring for the Sick

Treating the thousands of Canadians who were stricken with the Spanish Flu became the responsibility of cities, towns, families and individuals — there was no assistance from the federal or provincial governments. Treatment simply consisted of quarantining the patient and keeping them comfortable. There was no vaccine.

Advertisements, issued by the Provincial Board of Health, appeared in the local newspaper advising how people could care for their sick family members. “Since thousands of people are nursing influenza patients in the province, the following instructions will be of value,” cites an ad which ran in the Okotoks Review in November of 1918.

View the full ad (PDF)

Instructions included fresh air, three days’ rest after fever breaks, keeping the patient away from other cases, providing nourishing food and plenty of water. It also suggested “unworried service; avoid chattering, nagging or questioning; and to anticipate wants of sickest patients.” It further added, “All bags, napkins, scraps of uneaten food, mouth swab, etc. should be wrapped in clean newspaper before being carried to the kitchen to be destroyed by burning.” It also advised that all linen, including masks and towels, should be boiled for five minutes. Attendants must be constantly masked and wear big over-aprons in the patient’s room, changing it to a different one before entering any other part of the house.

Okotoks residents were quick to help their family and friends as well as complete strangers. The Rev. and Mrs. H. H. Wilford of St. Peter’s Anglican Church along with Beatrice Wyndham were among those who volunteered to nurse members of the Sarcee First Nation located west of Calgary. “… nearly everybody there was down,” noted the Okotoks Review, “with hardly anyone to do the work [of] nursing, cooking or anything else.”

Meanwhile, Ernest and Alberta Daggett offered their home on Elizabeth Street in Okotoks as a hospital if necessary, with Alberta’s sister Lena offering her services as a nurse.

Unbearable Isolation

Adding to the stress of catching the flu was the isolation.

Residents were ordered to stay home and avoid all gatherings in streets, stores and other public places. Schools and churches were closed and a curfew was implemented. This meant many residents were cut off from knowing what was happening in their community. There was no radio yet (that didn’t come to Southern Alberta until 1922). A few others were able to keep in touch by telephone if they were fortunate to have one. For the most part, people living in Okotoks and the surrounding area relied on the local weekly newspaper, the Okotoks Review, for their news.

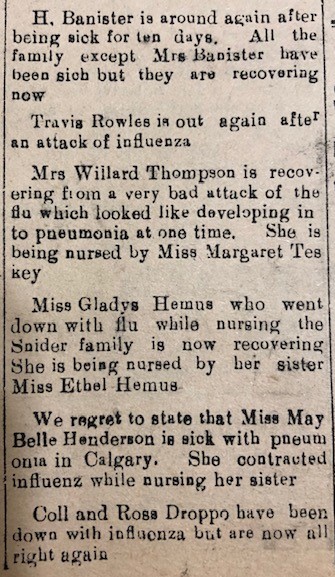

Every week, almost every page of the Review was devoted to the latest news about the Spanish Flu. It recorded by name all the people who came down with the deadly virus. Residents then fearfully waited for the next issue of the paper to read, with relief, if their friends and neighbours recovered or, with remorse, if they did not.

Great Losses

May-Belle Henderson of Okotoks was among those listed in the Dec. 27, 1918 issue as having contracted the flu while nursing her sick sister, Libbie. The next week’s paper shared the sad news of May-Belle’s death. “The deceased girl may truly be said to have given her life for other[s]. She went up to nurse her sister and family who were all down and was taken with the disease herself and was not able to go to bed herself till it was too late.” She was 24.

May-Belle was just one of several Okotoks and area residents who died from the flu. Herbert Merrick, Pte. Angus Gunn, Leander Tyndall, Mrs. Pete Murray and Ellen Nora Snider were among those who lost their lives.

Perhaps no family in this area suffered more than the Wakeford family.

Noah and Ida Wakeford boarded a local teacher, Miss G. Johnson, at their home east of Okotoks. In early March of 1919, Miss Johnson became ill with the Spanish flu; soon all members of the Wakeford family caught the flu. They had three nurses to look after them and the doctor attended to them every day. But there was little they could do. Within eight days, three members of the Wakeford family died: 15-year-old Clinton died first on March 21, mother Ida on March 27 and father Noah on March 29. Two remaining children went to live with an aunt and uncle. The Wakefords are buried in the Okotoks Cemetery.

Although churches were closed, funeral services were still able to be held. Some were conducted at Wilson’s Undertaking Parlour on North Railway Street in Okotoks, some at the Okotoks Cemetery, and some outdoors at the homes of the bereaved family.

“The flu epidemic took its toll on people of the district,” writes Estella (Bryce) Nelubowich in the history book, ‘A Century of Memories.’ “One day, Dr. Ardiel was making his rounds tending the flu victims. There were two young children playing outside the house. He asked where their father and mother were and they said they were ‘asleep.’ He went in and they were both dead from the flu.”

Stories of Survival

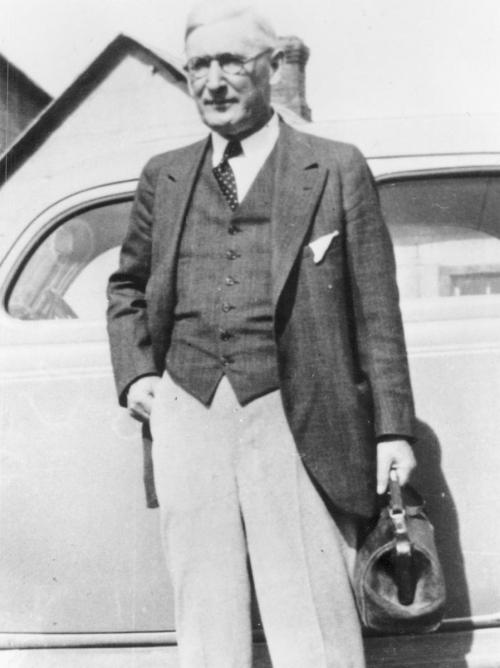

The physical and emotional toll on the town’s only doctor, Dr. Alfred Ardiel, must have been overwhelming. “Dr. Ardiel went down with a temperature last night,” reported the Okotoks Review on Dec. 20, 1918. “His temperature is down to normal this morning, but he will be confined to his bed for a day or two as he is completely rundown through overwork.” Dr. Ardiel recovered and went on to serve the community for another three decades.

Mr. and Mrs. Harold Smith and their children, who lived west of Turner Valley in the Lineham district, all came down with the Spanish flu in 1918. The flu turned into a severe case of pneumonia for Mrs. Smith. Just when they started to count their blessings having survived the flu, further tragedy struck: “Mrs. Smith was out of danger and recovering nicely when last night the house took fire and burned to the ground with all its contents. The family were hastily removed to some of the neighbours’ place but the shock and exposure are calculated to have a bad effect on sick people,” reported the Okotoks Review. No doubt.

Elizabeth Mattless came down with the Spanish Flu in the third wave of the pandemic. Her experience is recorded in the local history book, A Century of Memories. “The winter of 1919, Elizabeth contracted the infamous flu. The doctor visited her twice a day insisting that her husband give her hot whisky which in the end saved her life. She was confined to bed for six weeks. Later, when she recovered, her husband used to joke about her being drunk for six weeks!”

The third wave of the Spanish Flu ended on April 25, 1919. A handful of cases were recorded into 1920.